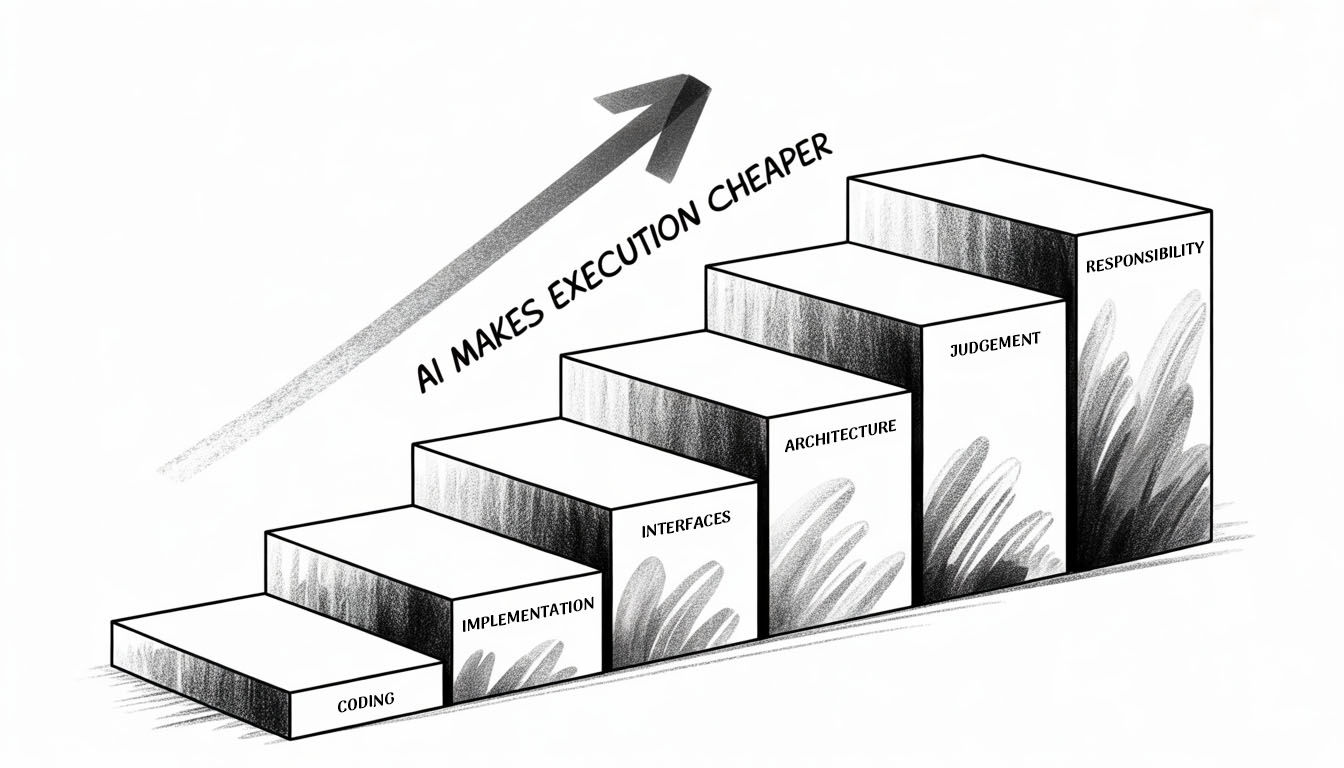

The arrival of generative AI has not eliminated the role of the software engineer. Instead, it has fundamentally reshaped it by pushing it upward in the abstraction stack.

The core value of the profession is no longer measured by the ability to write lines of code, but by the ability to design, reason about, and take responsibility for complex systems—systems where part of the behavior is non-deterministic.

This shift does not reduce the importance of engineering rigor. It eliminates it completely in some areas and makes it extraordinarily relevant in others.

From execution to delegation

Modern software engineers increasingly operate through a delegation model. Rather than implementing every detail themselves, they define tasks, constraints, and success criteria, and delegate execution to copilots, agents, and automated systems.

This changes the daily work in a subtle but profound way. Less time is spent typing code, and more time is spent thinking carefully about what needs to be built, why it needs to be built, and how correctness should be validated. Delegation is not abdication: even when most of the code is produced by AI, responsibility for the system remains in the human.

What matters here is not prompt cleverness, but engineering fundamentals: correct problem decomposition, well-defined interfaces, and explicit acceptance criteria. These are the levers that allow delegation to scale.

Architecture and requirements as the primary leverage

As execution becomes cheaper, requirements and architecture become the dominant sources of leverage.

Strong engineers invest heavily in understanding the problem space, making architectural trade-offs explicit, and tracing a plan before implementation begins. AI plays a key role here—not as a code generator, but as a reasoning partner. Engineers use it to ask questions about existing systems, explore alternatives, and build a precise mental model of how a system works and how it can be safely changed.

The competitive advantage shifts away from raw implementation speed and toward architectural clarity and judgment.

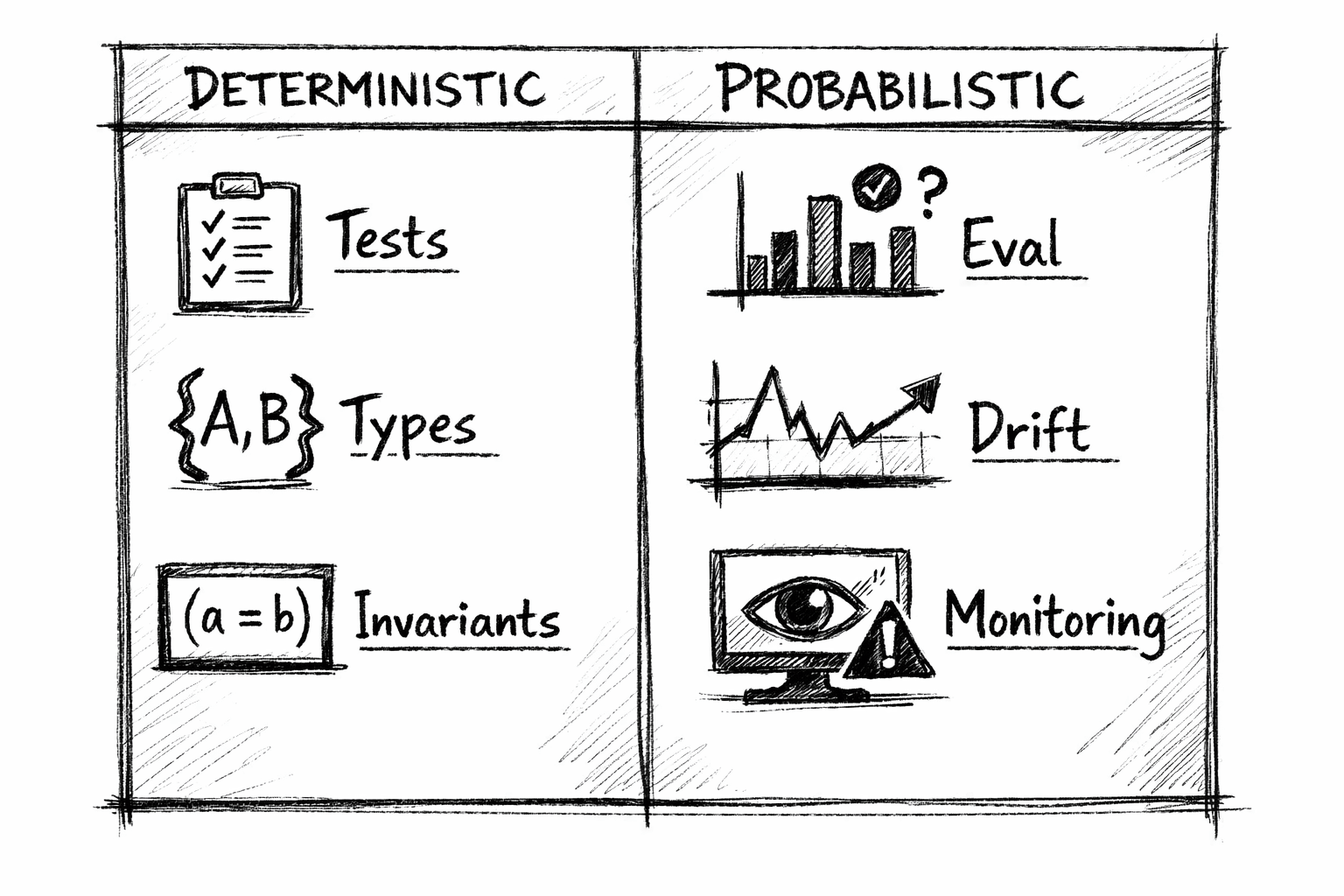

Deterministic foundations still matter—and matter more

Despite the rise of probabilistic components, a large portion of any system remains fully deterministic: business logic, data transformations, invariants, and critical execution paths.

In these areas, classical software engineering practices remain essential. Strict typing, strong compilers, unit tests, and continuous integration are not legacy habits—they are the foundations that make modern systems tractable.

As code is produced faster and in greater volume, these deterministic guarantees become even more valuable. They define clear contracts, catch errors early, and create safe boundaries within which both humans and machines can operate.

Deterministic validation as an accelerator for AI

There is an additional, often overlooked effect of these practices in the age of generative AI: they dramatically increase the effectiveness of coding agents themselves.

Systems with strong typing, explicit compiler errors, and clear test suites provide fast, unambiguous feedback. This feedback is not just useful for humans—it allows AI systems to iterate, self-correct, and converge on valid solutions with minimal supervision.

In such environments, the development loop becomes almost mechanical: generate, validate, fail, repair, retry. The technical stack, therefore, is no longer just an implementation detail. It becomes a strategic choice that determines how effectively AI can participate in the development process.

Non-deterministic systems require a different kind of rigor

The most significant change introduced by generative AI is the presence of non-deterministic behavior inside production systems. Model-based outputs, probabilistic reasoning, and context-sensitive responses cannot be validated with traditional assertions alone.

In these parts of the system, correctness is not binary. Instead, it is statistical.

This is where evaluations—or evals—become a core engineering skill. Rather than asking whether the system is correct, engineers ask how often it behaves as intended, under which conditions it degrades, and how stable its behavior is over time. Evals measure alignment, quality, and reliability in probabilistic terms, providing a quantitative handle on inherently uncertain behavior.

Observability, anomaly detection, and feedback

When systems are non-deterministic, visibility is non-negotiable.

Modern engineers design observability, anomaly detection, and feedback loops as first-class concerns. The goal is not merely to collect metrics, but to understand when the system is drifting, when assumptions are no longer holding, and when intervention is required—ideally before users experience failures.

This operational awareness becomes a central part of engineering judgment.

Data as leverage for continuous improvement

The outputs of evals and anomaly detection systems are not just signals—they are assets.

Engineers use this data to generate new datasets, refine prompts, compare models, experiment with alternative strategies, and decide when fine-tuning is justified. In doing so, they close the loop between production behavior and system improvement, turning real-world usage into a driver of continuous evolution.

Human judgment and reducing cognitive load

Even in highly automated systems, not all code deserves the same level of scrutiny.

Experienced engineers make deliberate decisions about where deep review is required and where lighter validation is sufficient. This selective application of attention is essential for maintaining quality without burning out human reviewers. Knowing where to focus is itself a high-value skill.

If there is a new hard limit in modern software development, it is not time—it is attention.

As a result, effective engineers aggressively reduce cognitive load. They rely on managed infrastructure, well-tested components, and external services to eliminate unnecessary complexity. Every concern that does not need to be reasoned about is a concern that cannot cause failure.

Choosing which problems not to solve becomes a critical engineering decision.

.png)

New constraints at the core of AI systems

This shift also introduces a new class of structural challenges that sit squarely in the engineer’s domain.

- Security becomes more complex when systems reason over sensitive data, invoke external models, and operate through agents that act autonomously. The attack surface expands: prompt injection, data leakage, model misuse, and supply-chain risks are now architectural concerns, not edge cases.

- Scalability is no longer just about throughput and latency, but about operating probabilistic systems at massive speed—where small degradations in model behavior can amplify rapidly under load.

- At the same time, customization complexity explodes: AI systems are expected to adapt to more contexts, users, and edge cases than traditional software ever handled, forcing engineers to reason about many parallel “realities” within a single system.

- This is compounded by the sheer volume of data produced—logs, traces, evaluations, embeddings, feedback signals—which must be stored, governed, and turned into insight.

- And finally, there is cost: AI introduces a new, highly variable cost structure driven by model usage, inference patterns, and experimentation cycles. Managing these constraints—security, scale, complexity, data, and cost—requires architectural judgment, not tooling tricks. They are precisely the kinds of problems that automation cannot abstract away.

The rise of the all-stack engineer

One of the most counterintuitive effects of AI-driven development is that a single experienced engineer can now outperform what previously required a small, well-balanced team. This shift gives rise to what we can call the all-stack engineer.

With modern tooling, an individual engineer can parallelize work in ways that were simply not possible before. Multiple coding agents can run simultaneously across separate git worktrees, exploring solutions, fixing issues, or implementing features in parallel. The engineer’s role becomes one of coordination and judgment rather than sequential execution.

Just as importantly, this model eliminates a significant amount of communication overhead. There are no handoffs, no sync meetings, no context loss between design and implementation. A single person can hold the entire system in their head, make decisions quickly, and execute without friction.

In practice, this means that one engineer can now take a project from concept to production in hours, not weeks. A prototype can be built, deployed, and exposed to real users within a day, with overnight validation providing immediate feedback.

Once the concept proves valuable, the team can scale. But even then, speed is maximized by minimizing overlap between engineers. We have increasingly adopted a 1 engineer : 1 project mantra. This does not mean isolation or lack of collaboration; it means organizing work as small, self-contained chunks of work where a single engineer is responsible for research, planning, implementation, testing, and deployment end-to-end.

This approach preserves autonomy, reduces coordination costs, and dramatically increases throughput—while still allowing collaboration at the boundaries when it truly adds value.

Responsibility does not disappear

Despite the increasing role of automation and probabilistic systems, responsibility remains firmly human.

Engineers are accountable for understanding system limits, managing risk, and responding to failures. The role has not become smaller—it has become more abstract, more strategic, and more demanding.

A threat and an opportunity.

This transformation represents a threat for software engineers that don’t adapt quickly to the new reality. And it represents a profound opportunity for those who do.

Two main factors should be taken into account:

- Software complexity is compounding. We are creating more software faster than ever before. And everything is interconnected.

- Software becomes more relevant. Our lives will depend even more on software than ever before, because now it will be present in places where before it couldn’t.

Those who embrace these new practices—delegation, architectural reasoning, statistical evaluation, rigorous validation, and high-autonomy execution—can create an impact an order of magnitude larger than before. Deeply experienced engineers are in a uniquely strong position: their understanding of system internals, their intuition for sound design, and their awareness of security, reliability, and scalability constraints allow them to guide AI-driven systems effectively.

Rather than being displaced, strong engineers become force multipliers. By combining hard-earned engineering judgment with generative tools, they can build better systems faster, validate ideas earlier, and move from concept to production with unprecedented speed.

The engineer is not dead. The engineer has to evolve, and their leverage has never been higher.